Dissecting the Sombrero Galaxy with Powerful Telescopes

A recent image taken by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) of a well-known object called Messier 104 (M104) helps us understand how much we can learn from powerful telescopes observing distant objects in different types of light.

Image Credit -NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Hubble Heritage Project (STScI, AURA)Getting its name

Discovered in 1781 by P. Méchain, M104 is also known as The Sombrero galaxy. Like many other objects, the name comes from its appearance in the sky. Oriented almost edge-on, it looks like a sombrero when observed in visible light by some telescopes. Its disk would be the wide brim of a hat decorated with a brim binding made of dust. Ignoring the light under the disk, the bright region at the center mimics the crown of a hat.

Changing the picture with Hubble

More powerful telescopes like Hubble later showed a slightly different scenario. The center is not an extended region; instead, it is a relatively small and bright bulge surrounded by an elliptical-like hallo that extends almost to the edge of the disk. The dust lanes at the edge are now clear. Extending towards the inner region, these intertwine with the gas in the disk. In the Hubble images, astronomers also resolve about 2,000 globular clusters, much more than the number of globular clusters in our Milky Way Galaxy[1].

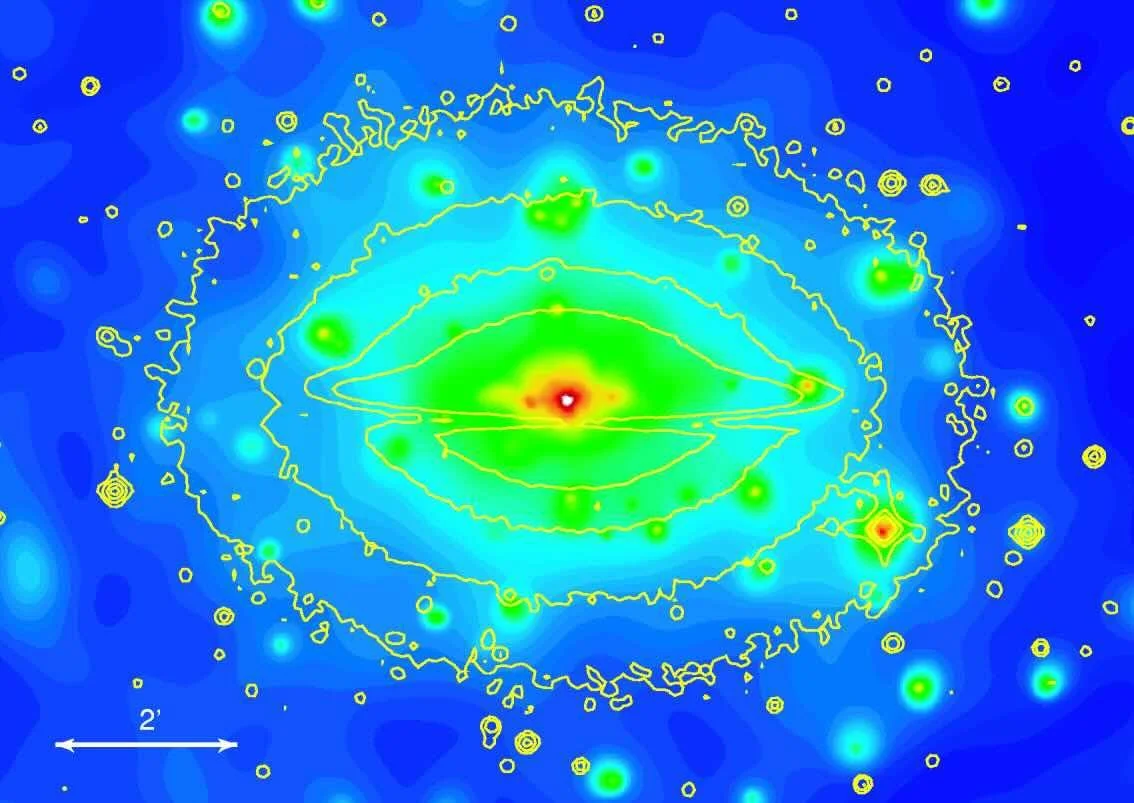

The view in X-rays

From observations made in the X-rays with XMM-Newton and Chandra, astronomers encounter evidence of material falling into the compact core, probably due to a central black hole with 1 billion solar masses[2]. Radio observations further suggest the presence of a ‘relic’ radio lobe, most likely from a previous episode of active galactic nucleus (AGN) activity. With these observations, astronomers conclude that M104 is a `radio-loud’ Seyfert galaxy or a low luminosity AGN[3].

Image Credit -Pellegrini et al. 2003The infrared observations

The infrared observations support the results derived from the X-ray observations and clarify what is happening in the disk. The infrared observations taken with Spitzer in 2005 reveal a compact core surrounded by a disk and an outer smooth ring, what they call a “Bull’s eye” configuration[4]. Putting together Spitzer’s infrared and Hubble’s visible light, we now see how far the dust extends into the disk.

However, thanks to the recent observations of JWST, we can go even further. The mid-infrared light taken with MIRI clearly shows the structure of the disk. The outer ring is not smooth but instead has a clumpy structure. Because MIRI’s emission arises from Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PHAs) or carbon-containing molecules, we know there should be star formation within the ring. However, it must be happening at a rate about half that of the Milky Way[5].

With JWST, we can also have a better view of the bright AGN. We can see a compact object in the center surrounded by a bright disk. In between the center and the outer ring, we can also see the dim disk observed by Spitzer. In this case, the bulge or stellar hallo that contributes to the crown of the Sombrero seems less extended and dimmer than that in Spitzer’s images.

These observations and those obtained with telescopes observing a different type of light will add to the puzzle pieces. Eventually, we will have a complete picture of what is happening in the Sombrero galaxy.

References:

[1] https://science.nasa.gov/mission/hubble/science/explore-the-night-sky/hubble-messier-catalog/messier-104/

[2] Pellegrini et al. 2003 The Astrophysical Journal 597 175.

[3] Kharb, P. Et al. 2016, MNRAS, 459, 1310-132

[4]https://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/image/ssc2005-11a3-spitzer-spies-spectacular-sombrero

[5] https://webbtelescope.org/contents/media/images/2024/137/01JCGK31M1TXEW8T7PEHHVDDC9?news=true