Dr. Néstor Espinoza – an expert in exoplanets

Credit: R. Diaz

Being able to talk about Dr. Néstor Espinoza is a privilege. A quite intelligent astronomer from Chile, he is now the group leader in charge of exoplanet science at the Space Telescope Science Institute ( STScI). Talking with Néstor is quite an experience. He is humble, super nice, and not afraid to talk about successes, failures, and what he has learned from them. His story may seem familiar to many boys and girls now studying high school or university careers. I hope his story inspires those, regardless of age, who dare to hold on to their dreams and make what may now seem impossible a reality.

Just a normal boy

Néstor remembers his childhood as full of friends, games, sports, and educational activities. Thanks to the support of his mother, who instilled in him to do many things, he always remained active. Néstor remembers playing roller hockey for many years. As he says, in general, a very normal childhood.

At that time, he never imagined being an astronomer. In his pre-adolescence, he thought he would be a lawyer. He loved debating with people and thought he could make a profession out of it. He also considered studying “Musical Interpretation,” a career I was unaware of but apparently had to do with interpreting music with the guitar. After listening to one recording from Néstor on the internet, I imagine he would have been very good at doing that, too.

However, Néstor remembers falling in love with physics in high school. Predicting how a ball falls or knowing why water evaporates seemed super entertaining, magical, and fascinating. Still, science was something distant for him, as distant as being a rock star, something that NASA did and appeared only on television.

The path to astronomy

Fortunately, when he was in high school, his physics teacher, Isabel Espinoza, learned about his love for science and opened his eyes to the idea of becoming a scientist. Nestor comments:

“My physics teacher mentioned that [doing science] was a career. That someone could pay you to do research. That seemed crazy to me. I found it almost magical, and I didn’t believe her. How is someone going to pay you to do research?”

One of the careers she mentioned was astronomy, and Néstor decided to become an astronomer. However, achieving his goal was not so easy. After taking the exams required to enter the university, Néstor did not reach the level necessary to register to study astronomy. He chose to study mathematics instead, with the idea he would transfer later to astronomy.

However, Néstor confesses that the first semester was terrible for him. As he says, “Mathematics was also difficult.” But in this case, it was not the level of the classes but his studying method. He realized that, at the university, he could not wait to hear what to study. He had to find a way to learn by himself, go to the library, and know which books to read and which not to read. From that moment on, everything changed, and he started to do well. Soon enough, he was able to switch to a career in astronomy, finishing promptly his undergraduate (or bachelor’s degree) and doctorate at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

The focus on extrasolar planets

Like all sciences, astronomy includes many complicated topics that can only be thoroughly studied when one focuses on one topic. Therefore, Studying for a doctorate requires choosing a particular area. Néstor chose to study extrasolar planets.

Since childhood, Néstor has been interested in aliens, flying objects, planets, and other civilizations. But the more he sought to know, the more he learned that there were no answers, that he could not quantify them or find evidence that they existed. When he entered college, he thought he would focus on another subject. However, it was not until his third year in college that he learned that studying planets beyond our solar system was an area of astronomy and that he could focus on that.

His passion for the subject intensified after taking an ” Exoplanets ” class with Professor Andrés Jordán. Néstor confesses that attending his class was not his first choice. By then, he preferred to prepare for the exams by reading the material alone and not going to class; however, this topic was so new that there were no books to read.

To his surprise, the classes were very entertaining and educational, and he learned a lot about the topic through discussions about recent articles. After finishing the course, Néstor remembers knocking at Andrés Jordán’s door to ask him for some work on any of his projects, even if it was something small. His enthusiasm and persistence probably convinced Andrés Jordán to put a project for him in the university’s summer internships. Not only was Nestor able to achieve his dream of working on this topic, but it was also the first time he got paid to do astronomy. He was so delighted to work with Professor Jordán that he ended up doing his PhD under his tutelage.

Thirteen years ahead

Artist concept of WASP-39b. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

Currently, Néstor and his team of collaborators are studying the atmospheres of other exoplanets such as that of WASP-39b. Thanks to the power of JWST, research into extrasolar planets has become even more exciting. Astronomers like Néstor can now take another step in the quest to study these objects and try to answer the most exciting questions on the subject — Do atmospheres like ours exist? Will those atmospheres have life?

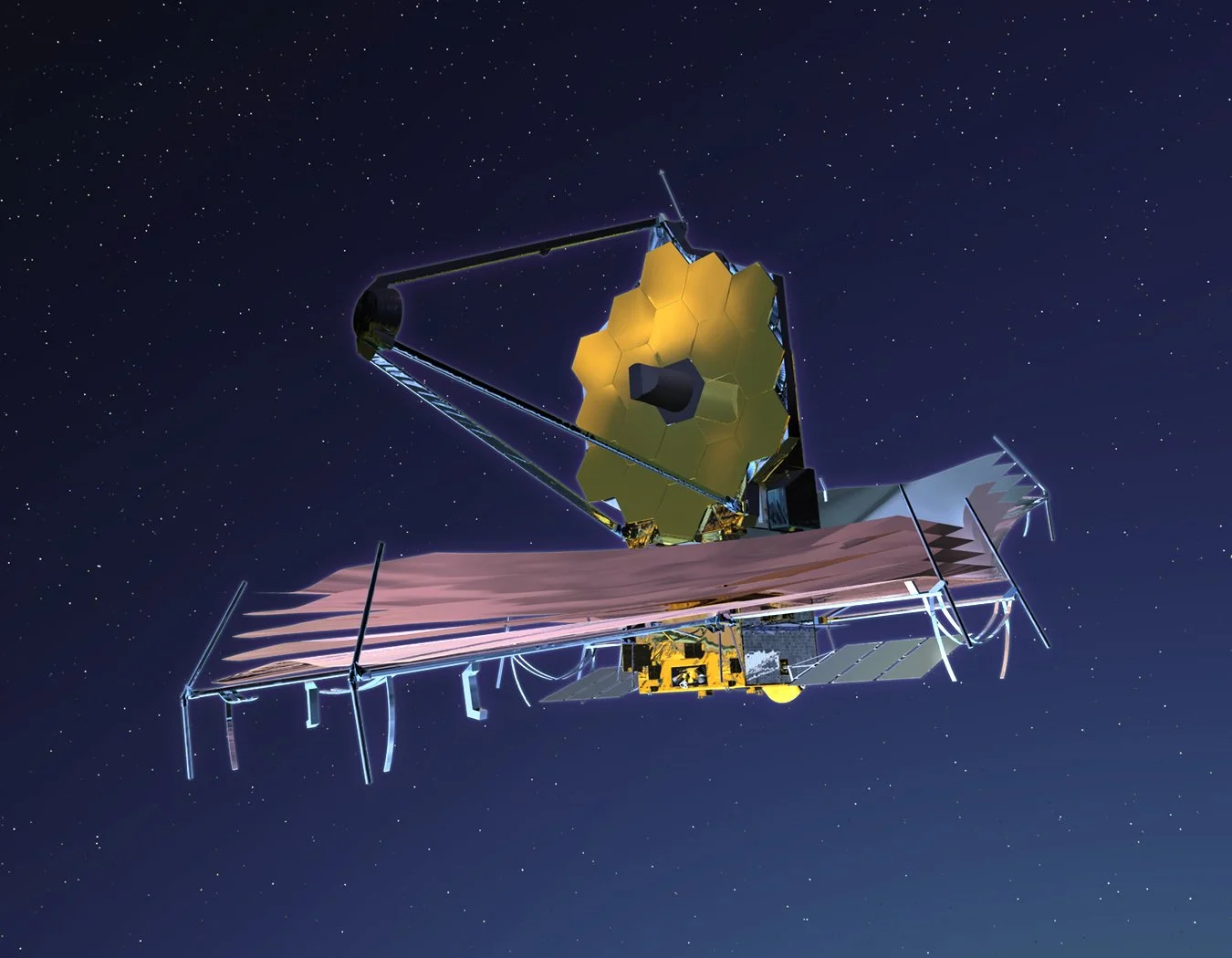

Working with James Webb

Working with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was also a dream come true for him. In Chile, as in other Latin American countries, projects of this caliber are difficult to achieve, mainly due to their high cost and the technology needed. However, data from JWST and other NASA telescopes are available to researchers worldwide, including researchers in Latin America. That’s why when he was in Chile and learned about the JWST project, Néstor was waiting for the moment when he could see some of this data or even propose observing with it. What he never imagined was that he would be part of this project.

Néstor acknowledges that working with JWST has also changed his thinking about projects. Setting up this large telescope that can observe in the infrared may have seemed crazy to many, but now we know that was not the case. — “To achieve a project of this magnitude, you must solve huge problems. You only achieve that when you have a diverse group (astronomers, engineers, optics experts, etc.) with different points of view and experience.” NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), the Canadian Space Agency, and a team of professionals from many countries and disciplines collaborated to make it possible. Néstor points out something eye-opening

“If you put a group of astronomers around the table who think the same way, you wouldn’t be able to solve [or design a telescope like JWST]. No matter how difficult the goal seems to be, it is possible if you have the right team.”

Now that JWST is in orbit and taking images, Néstor dedicates 50% of his time to helping the scientific community with their observations. Supporting observers is essential since doing science with JWST is not that simple. To take and extract scientific results from observations necessitates having a deep knowledge of the instruments, the telescope, and the software used to extract the data. Without support from scientists like Nestor, astronomers would not know how to use JWST, and it would take years to extract actual scientific results from their observations.

Exoplanet Science

Even now, studying extrasolar planets is still considered a very young topic. When Néstor began his studies, the topic started to expand thanks to the discoveries of the Kepler space telescope. This telescope, launched in 2009, aimed to find Earth-sized planets that were in “habitable” regions, that is, neither so far nor so close to their star that they could have liquid water.

So far, thanks to Kepler, astronomers know about the existence of approximately 5,000 planets of many sizes (from around the size of Neptune to smaller than Earth). Kepler found that between 20 and 50% of the stars visible in the night sky may have small planets, perhaps rocky like Earth and in the habitable zone. Now, with the power of JWST, astronomers can observe these planets in great detail. In particular, with the spectra of their atmospheres, it is possible to decipher their chemical composition and determine how they compare to the planets in our solar system.

The image of a scientist

Many people have a romantic idea of what a scientist is. In movies or series, scientists are geniuses who spend all their time looking at the sky, writing on a blackboard, thinking deeply about things, doing experiments, and working alone. Néstor makes it clear that it is impossible to work alone in science and that you need to be very versatile to be able to solve problems. You have to be communicative, create a scientific community, and collaborate. The bigger the problem, the more people it takes to solve it, and this is something that Néstor loves to be able to do.

Néstor also shares his failed experiences and how he has learned from them. Considering that most people in science have to write proposals to obtain resources or data for their research, it is easy to understand how accustomed they are to rejection. For example, Néstor reminds us that only 10% of proposals submitted to observe with JWST are accepted.

But a rejection is not necessarily a total loss. There is always something to learn in each of the proposals, even the rejected ones. Néstor says it is like “a philosophy of life – there may be things that are very far away, but traveling the path will teach you a lot and perhaps make you see other horizons of other areas that might interest you as well.”

Néstor has learned a lot from the feedback he received from his rejected proposals, which has helped him improve future proposals. For him, the important thing is not to give up. Nestor comments

“Even if things seem very far away, I can do it. If someone else could, you can too. You must look for and take the opportunities because they will not come from the sky. “Sometimes it will require making sacrifices, but it will be worth it.”

Dissemination and mentoring work

For Néstor, the influence of his mentors was critical to getting to where he is now. That is why he always seeks to support young people who work with him or give talks that motivate future generations. On his trips to Chile, usually to visit family, he always looks for a way to give talks and connect with Chilean youth.

Something exciting he shared with me was the great privilege he received from a secondary school in Peñaflor, a community on the outskirts of the capital, Santiago de Chile. Recognizing his position in the astronomical community, teachers, parents and students of the “Liceo Peñaflor,” requested to name their new Astronomy Room after Néstor. During the inauguration, Néstor gave a talk and remembered with pleasure how both children and adults were happy to hear about his work, his discoveries, and his future projects.